Introduction

Sometimes it’s useful to call up a meeting with your personal board of directors when faced with difficult decisions. In this article, I’ll call in a few of mine to see what I can learn about the interplay of commitment and flexibility.

Tolstoy’s Young Man with a Big Problem

Nikolai Rostov was a young man with a major dilemma. He was betrothed to his cousin Sonya but he wasn’t in love with her. After returning home from the war in Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, he told his sister (paraphrasing here) “I’ll never go back on my word, but…Sonya is so young…and how can I be certain that I won’t fall in love with another?”

I know that struggle. We’ve probably all had thoughts like these: “Sure I’m interested in this now, but can I commit to studying it for years, possibly building my career around it?" Or, “Sure I really like this person, but am I ready to commit to a serious relationship?".

Commitment and flexibility are both good qualities but they seem to collide in confusion when it comes to making decisions.

David Brooks' Vampire Problems

Knowing myself as I am now is hard enough but trying to predict what I’m going to be like in the future is like trying to think of a billion.

David Brooks describes this predicament as having “vampire problems”1. Imagine someone tried to sell you on becoming a vampire. Benefits include super strength, living to see the centuries of man pass, and the ability to fly (that would probably do it for me). You’re able to get blood from cows or something. And a bunch of your friends have already made the switch and urge you to join them.

But even after making a pros and cons list, you still will never know what it’s like until you’re there. Sure you could have an interview with a vampire but that might not work out well for you (pun intended).

It’s clearly not like trying to decide which pair of shoes to buy. Once the die is cast there’s no going back. Brooks puts commitment decisions in their most serious light:

“Every choice is a renunciation, or an infinity of renunciations. You will be forever after aware of the road not taken, what might have been if you’d gone another way. You could be opening yourself up to a lifetime of regret."1

Those kinds of stakes just shut down my brain. There must be some kind of middle path.

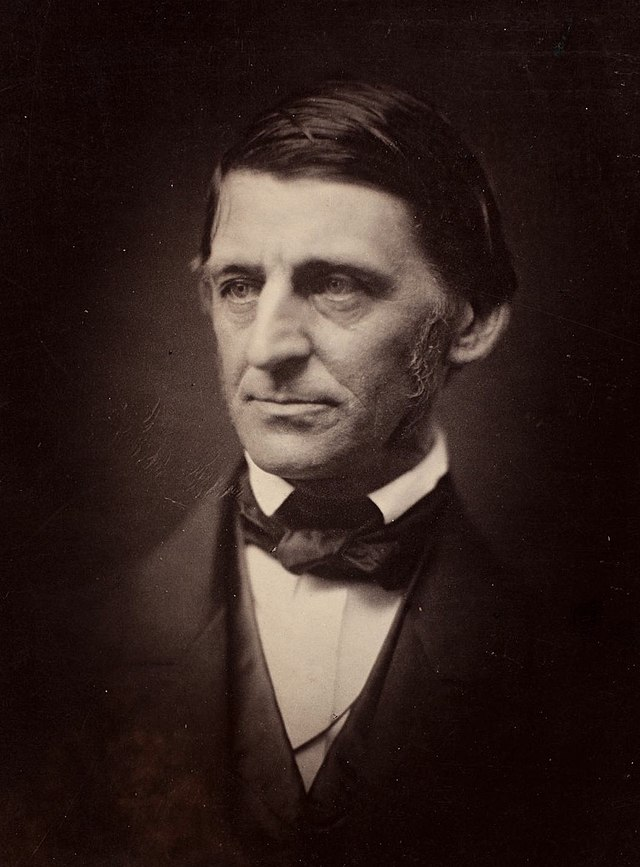

Emerson and The Conservative

Twenty-four years before Tolstoy published his masterwork War and Peace, and 147 years before Brooks wrote The Second Mountain, Ralph Waldo Emerson was working on such a synthesis. In a short essay called The Conservative, Emerson characterizes conservatism (having a different meaning then) as a negative force, resisting change at all costs. It “makes no poetry, breathes no prayer, has no invention; it is all memory.”

Emerson’s conservatism is like a commitment: it exists to conserve and protect something. But reform is always banging on the door demanding change. He writes that reform has “no gratitude, no prudence, no husbandry.”

He finds a splendid blend of these two clashing forces using the transcendental language of nature. Speaking of conservatism and reform, he writes:

“Each exposes the abuses of the other, but in a true society, in a true man, both must combine. Nature does not give the crown of its approbation, namely, beauty, to any action or emblem or actor, but to one which combines both these elements; not to the rock which resists the waves from age to age, not to the wave which lashes incessantly the rock, but the superior beauty is with the oak which stands with it hundred arms against the storms of a century, and grows every year like a sapling…"2

A true man is one who “has subsisted for years amid the changes of nature, yet has distanced himself, so that when you remember what he was, and see what he is, you say, what strides! what a disparity is here!"2

Emerson believes these two polar opposites can find harmony within nature and within us, making us true and beautiful. Sounds promising! But how do I do it?

“What if there is no tomorrow?”

This idea of a man living apart from society but growing reminds of one of my favorite movies, Groundhog Day. Phil Connors is a jerk weatherman who is suddenly and inexplicably trapped in a day that he must repeat seemingly forever. Every morning at 6AM, everything and everyone are reset except him.

It’s a funny yet moving film that demonstrates the power of internal growth and change regardless of the environment.

Phil became Emerson’s growing Oak. He was rooted in Punxsutawney but went from a jerk to one of the most beloved men in town. Perhaps even forced commitments hold opportunities for transformation.

“Know thy [values]”

We naturally don’t want to be trapped like Phil or chained down like Prometheus. We want freedom and flexibility too. Theologian Tim Keller remarked that freedom “is not so much the absence of restrictions as finding the right ones.” And you need to find what is right before you can make promises to it.

The commitment you want is a joy; the commitment you don’t is a burden. So perhaps step zero is figuring out what it is you want, what you value most. If you don’t know, take some time to climb and discover.

I believe this devotion to our values is where love and passion need to burn brightest. It’s this passion – to act even when we’re not sure of the outcome – that will keep us from a Kierkegaardian “crudeness”3, a dull life devoid of animating enthusiasm.

Perhaps flexibility isn’t the enemy of commitment, but a necessary condition for commitments to last. Conflicts are inevitable: “I really want to play guitar right now, but I need to get ready for work.” Flexibility says, “Well I’ll play tonight after work.”

We need commitment to do the work and flexibility to make it work.

Afternote

I wrote this essay to help organize my thoughts by drawing on better minds and ideas around commitment and flexibility. It’s a real question in my life at the moment. I’m currently separated from my wife and it’s an open question if I should re-commit given our past 11 years together and not knowing, like Nikolai Rostov, if new bright love is out there. Someday I know I’ll understand it more. I just hope it doesn’t take as long as Phil Connors.4

-

Brooks, David. The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life. First edition. New York: Random House, 2019., 106-107 ↩︎

-

“Emerson–“The Conservative”.” Accessed October 6, 2022. https://archive.vcu.edu/english/engweb/transcendentalism/authors/emerson/essays/conservative.html. ↩︎

-

Kierkegaard, Søren, Howard V. Hong, Edna H. Hong, and Søren Kierkegaard. Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age: A Literary Review. Kierkegaard’s Writings 14. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1978., 62 ↩︎

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groundhog_Day_(film)#Time_loop_duration ↩︎