Almost 2400 years ago, one of the greatest revolutions the western world has ever known set off.

It was a relatively quiet explosion, not a famous battle or the overthrow of an empire. It was a young man watching his hero, teacher, and mentor put on trial and condemned to death. His teacher had dedicated his life to questioning others, for, as he put it, “the unexamined life is not worth living.”

This was the trial of Socrates in Athens, Greece. Socrates never wrote his beliefs, preferring face-to-face discussion. Yet 2400 years later, almost entirely thanks to Plato, the young man at the trial, Socrates' name is ubiquitous.

Plato grew up in the shadows of the heroes of Homer. He came from a well-to-do family in Athens, was well educated, a good wrestler and had political career opportunities.

But after meeting Socrates, Plato found higher truth in the wisdom of a poor older man’s mission to seek to understand what makes the best human life. Plato devoted his life to uncovering truth and knowledge. His intellect matched his acute sense of moral obligation to improve his countrymen and the world.

Athens was not without standards and idols for human perfection. For centuries, Greeks revered Homer, the epic poet. The dramatic characters and heroism of men like Achilles, Ajax, and Agamemnon were Greek civilization’s bedrock. Their deeds set the standard for bravery, virtue and manly action. These heroes were the role models of physical strength and daring in a time when war and violence were common and where winning meant survival.

Plato saw a defect in his culture. How honorable and virtuous could Athens be if it voted to execute a man like Socrates? What good is all that poetry if it inspires bravery and honor while failing to denounce the darker sides of human nature: greed, murder, cruelty?

For Plato, it was time for a revolution.

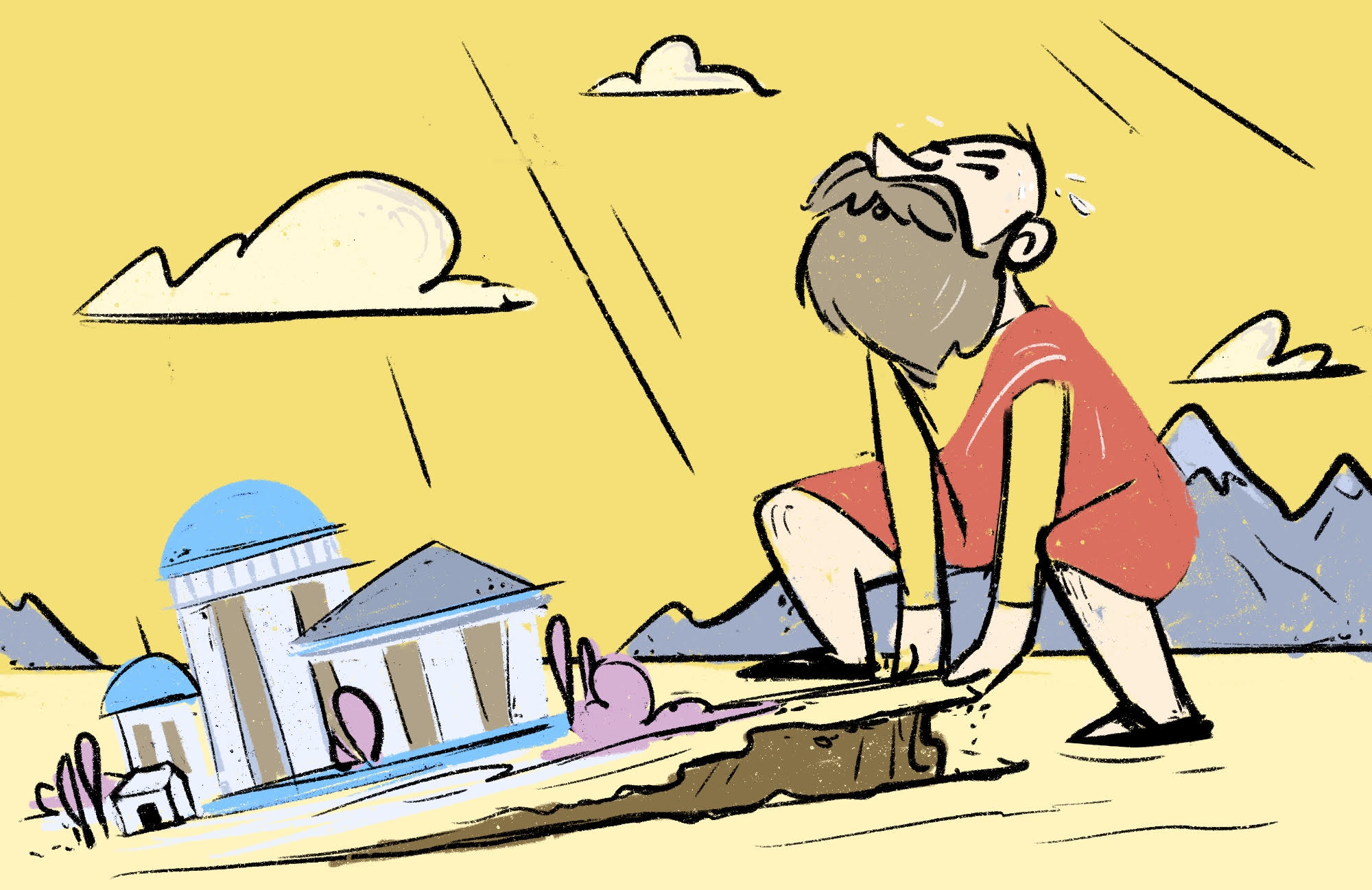

Plato wanted to shake things up in Greece.

His revolution was not to be founded in military conquest or glory. Unlike Homeric heroes, Plato undertook the more difficult task of a cultural and moral revolt.

Plato took aim at the poetry of his day for its haphazard mixture of cruelty with courage and its failure to teach morality and good conduct.

Plato didn’t just criticize. He shared his visions for the perfect form of a society, one that would be most conducive to human happiness and excellence, in The Republic.

In a perfect state, a society’s art would only be edifying.

“We would not have our guardians grow up amid images of moral deformity, as in some noxious pasture, and there browse and feed upon many a baneful herb and flower day by day, little by little, until they silently gather a festering mass of corruption on their own soul.“

Plato is fine with the arts so long as it doesn’t cause bad behavior. In other words, he wants Homer “house-broken.” He tried to set up better examples for his countrymen so that

“They should imitate from youth upward only those characters which are suitable to their profession – the courageous, temperate, holy, free, and the like; but they should not depict or be skillful at imitating any kind of illiberality or baseness, lest from imitation they should come to be what they imitate..”

For Plato, it was moral turpitude, not Socrates, that corrupted the youth of Athens. So Plato put both hands under the foundation of Homer, with all its good and evil, and tried to raise his country to a higher moral plane.

After over 30 written dialogues, a new hero of truth and virtue starring Socrates, and an Academy for teaching his ideas in Athens, Plato’s full-scale revolution against centuries of moral deficiency was underway.

But would it succeed?

Plato had tipped the dominos for the western world everlastingly. He heavily influenced Aristotle, and both would inspire countless secular and spiritual thinkers. The revolution to a higher life still reverberates down the halls of governments, churches, and schools throughout the world today.

Some of Plato’s ideas have been rightly refuted and left in antiquity. Indeed many of Plato’s ideas for a utopian society would strike the modern American as cringeworthy and communistic.

Yet, despite some of his ideas being abstract or delusional, Plato has remained relevant for millennia. While we would mostly disagree with him today on how to create a better society, we would mostly agree on the why. The ages have edited his means, but his end endures.

And this end has always been a personal one. Moments before Socrates' death, Plato, speaking through Socrates, invites us to his cause:

“One must make every effort to share in virtue and wisdom in one’s life, for the reward is beautiful and the hope is great."

Plato understood our tendency to elevate idols and honors that mislead us from true knowledge and joyous living. He presented a different kind of hero who showed us how to conquer ourselves instead of others.

The criterion for Plato’s success has remained the same after almost two and a half millennia - whether Socrates needles us still with his questions.

We don’t need to become platonists to be a part of that revolution. For our part, we can renounce toxic cultures obsessed with materialism, achievement and monetary gain in our day and age. We can venerate and appreciate heroes who exemplify virtue in everyday living. They are all around us.

And perhaps most importantly, we can be satisfied living an uncelebrated ordinary life, so long as it is an examined one.